Reuben (Richard) Meyer marked the festival of Hanukkah

in 1945 far from his wife, Judith, and their two young children, Amatzia and

Nurit. At the time, he was serving as a physician in the Ninth Army of the

British Army, which was stationed in India. He maintained a correspondence with

his family in Palestine, and among the letters are Hanukkah greeting

cards - a holiday that was particularly dear to him.

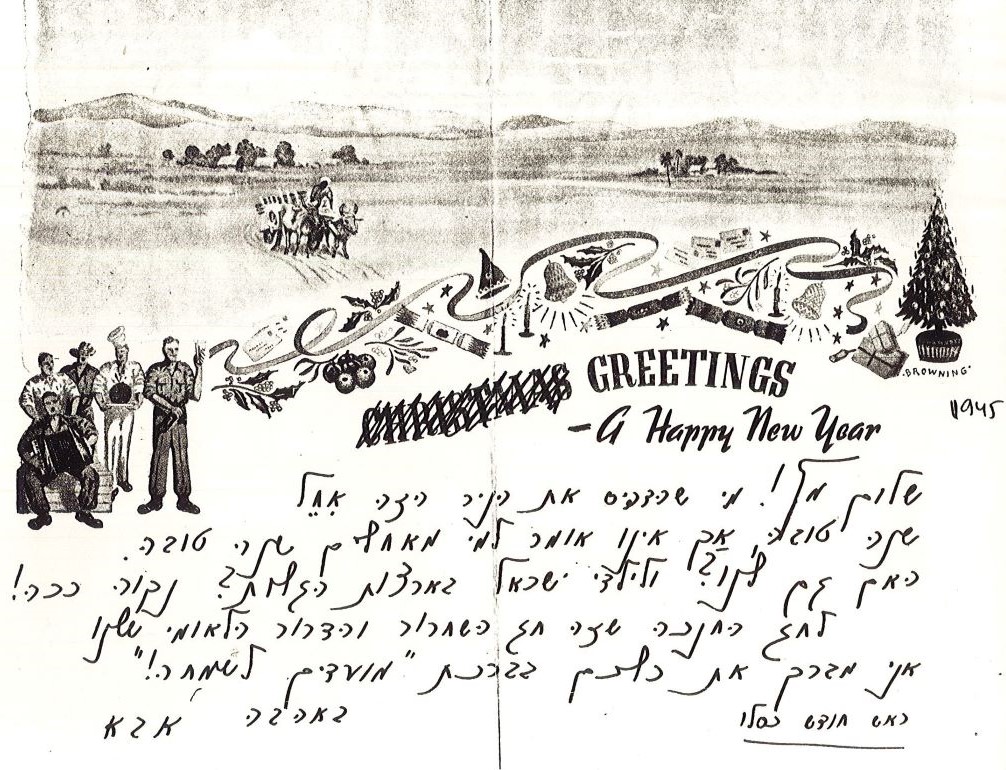

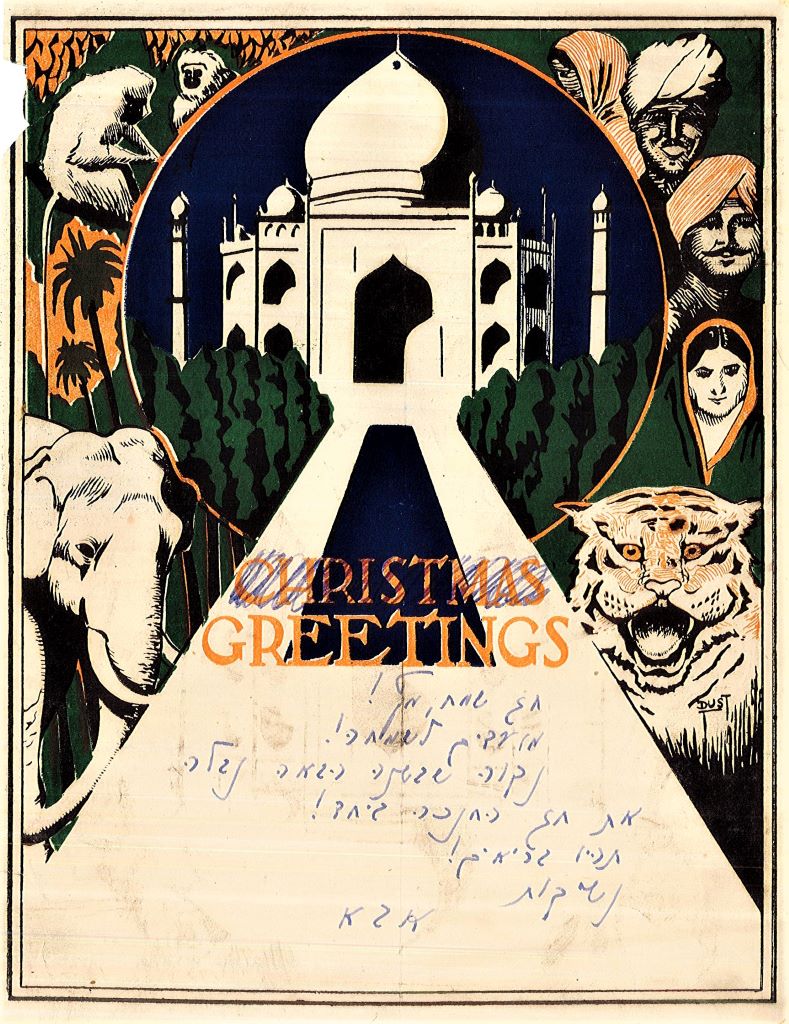

On a Christmas greeting card that was sent by airmail

from India, Reuben Meyer wrote to his eldest son, Amatzia:

“The person who printed this paper wished a ‘Happy New

Year’, but does not say to whom the good wishes are addressed.

To us as well? And to the children of Israel in the

lands of exile? Let us hope so!

For the festival of Hanukkah, which is our festival of

national liberation and freedom, I bless you all with the greeting ‘Joyous

Holidays!’”

Since Hanukkah greeting cards were not available, Meyer

had no choice but to send greetings designed for Christmas - after first crossing

out the word Christmas with a pen and adding the name of the Jewish

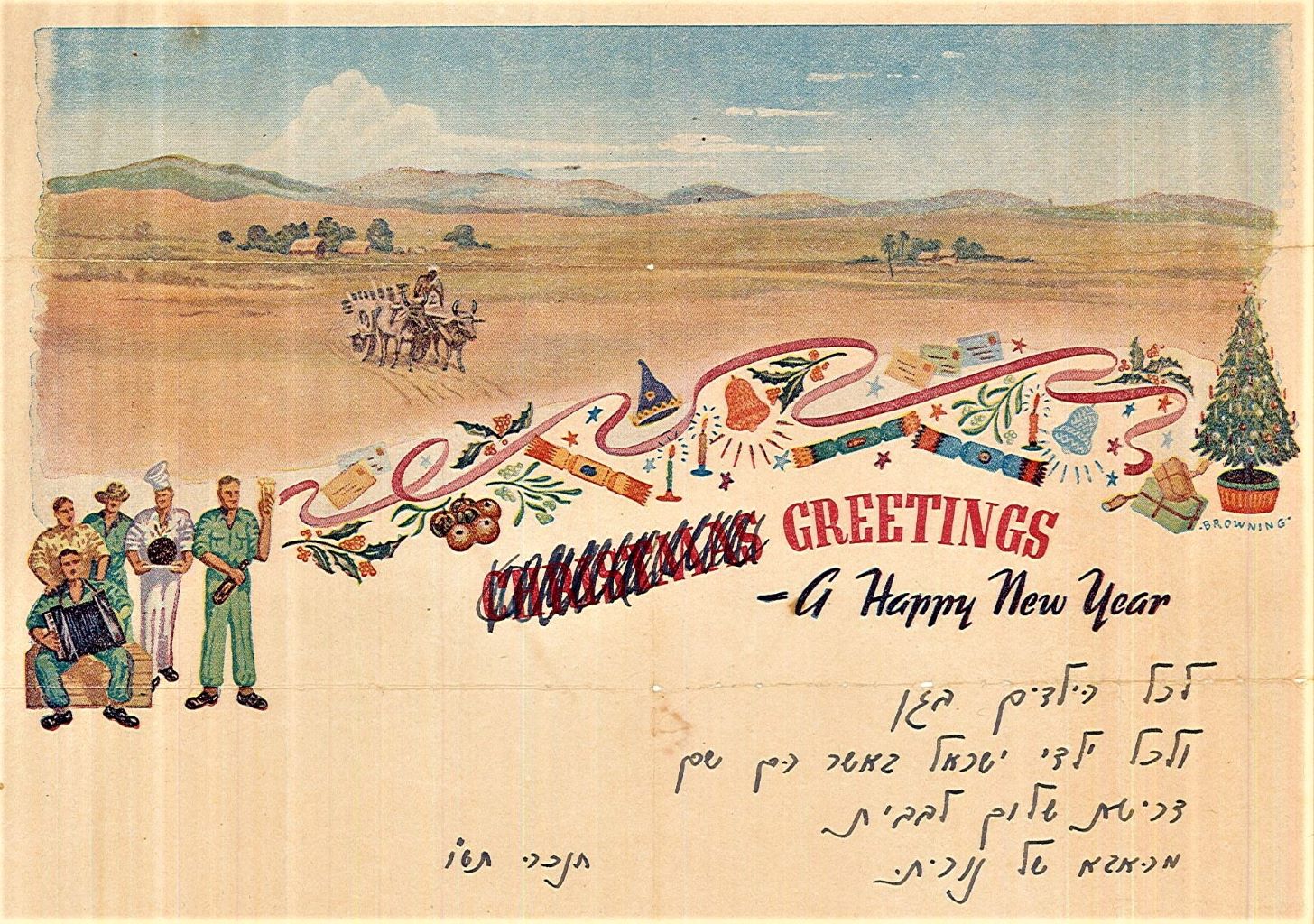

holiday. He also sent an illustrated card to the kindergarten children of his

younger daughter, Nurit, so that she could share her father’s experiences in

distant India with her friends.

Greetings from Reuben Meyer to Amatzia, 1945 (A628\13)

New Year greeting card with regards from Reuben Meyer to

the kindergarten of Nurit, 1945 (A628\13)

The story of Reuben Meyer begins in Germany. He was born

in Berlin in 1908, studied medicine, and specialized in surgery at the

municipal hospital. In the first year of his residency, the Nazis rose to

power. Fearing the fate awaiting German Jews, Meyer decided to immigrate to Palestine as quickly as possible. After

arriving in Palestine as a tourist, he sought to secure permanent residency and therefore

enrolled at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. He could not later recall exactly

which academic track he registered for since he never truly intended to return

to his studies, but he did receive the permit.

His medical studies in Germany did not help Meyer find

work. He took on temporary jobs in

construction and agriculture, using the time to improve his Hebrew. A year

later, he began working in Tel Aviv for a meager salary with a department head he had known from the hospital

in Berlin, who had just immigrated himself. That same year, Reuben married Judith, secretary of the

Second Maccabiah Games. Through her, he learned that the company Hakhsharat HaYishuv was seeking a physician to work in Be’er Sheva, and he seized the

opportunity. Yehoshua Hankin, the company’s director, explained that as part of

establishing Jewish settlement in the south, they needed a doctor who would

serve the Bedouin population and help foster friendly relations with them. The couple established positive relations with the Bedouin, and the clinic was successful. However, following the outbreak of the Arab riots of 1936, they were forced to leave.

Reuben and Judith Meyer, circa 1958 (A628\1)

Reuben’s financial situation did not improve, and he

accepted an offer from the British authorities to enlist in the army. When he

was drafted, Judith remained at home with their two children: Amatzia, aged

four, and Nurit, six weeks old. Meyer trained in a medical officers’ course in

Palestine and was then sent to Syria and Lebanon. In early 1943, he was posted

to the British headquarters in India, where he served as a physician alongside

forces training for the invasion of Japan.

The Hanukkah holiday at the end of 1944 was

particularly joyful for Meyer. In an autobiography he later published, he

described how he was unexpectedly assigned to organize the holiday observance

in his unit:

“From wooden rods and beer bottle caps I made a Hanukkiah. I spread a white sheet on the table in my living hut, and

from funds I received by order of the commander from the unit welfare fund, I

prepared candles and light refreshments, and we celebrated Hanukkah.”

(From January 1933 Until This Day: An Autobiography,

Dr. Reuben Meyer, self-published)

Letter to Amatzia with Hanukkah greetings and Reuven’s hope to celebrate

with his family the following year (A628\13)

On the reverse, Reuven added: “Greetings and kisses, Father” (A628\13)

Meyer sent many letters to his wife and children

throughout his service in the British Army. The letters are filled with charm,

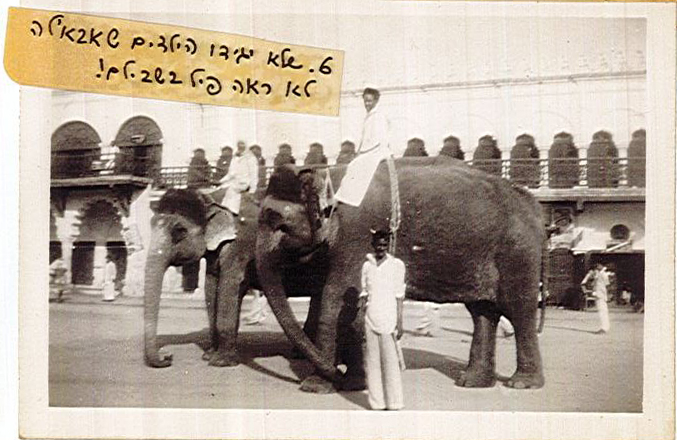

humor, and deep longing for his family. In a small pocket album, he kept

photographs from India, and beside them he wrote captions for his

children explaining scenes typical of Indian streets. At the beginning of 1945,

he wrote to Judith about the joy he felt that little Nurit remembered him

despite his long absence:

“I am very, very happy to read in your letters that

little Nurit remembers me. As for Amatzia, that is different. After all, we

lived together for four years, and when I left home, he was already a person,

and he saw me from time to time. But the little one? What could she

possibly remember about me! I am very happy!”

.jpg)

Letter from Meyer to his children, in which he amusingly explains how

to draw a circle (A628\13)

Photograph of an elephant in India. Meyer wrote beside it: “So the children won’t say that Daddy didn’t see an

elephant for them!” (A268\36)

After Japan’s surrender, Meyer sailed to England and from there returned to Palestine, reuniting with his family after three and a half years. In 1947, he began working

as a surgical physician in the clinics of Clalit Health Services in Haifa and

was involved in establishing medical services in the north ahead of the War of

Independence. Toward the end of the fighting, he served as a military doctor in

Jerusalem. After further training in England and the United States, he was finally able to secure employment suited to his qualifications. He specialized

in orthopedics, and in 1957 began working for the National Insurance Institute. Reuven Meir died in

Jerusalem in 1989.

Reuben Meyer’s archive was donated to the CZA in 2018 by his daughter Nurit, who became a

writer and illustrator of children’s books. The letters the family received

from their father during his service in the British Army were published by

Nurit in the book A Life of Paper. The Meyer Archive contains personal documents, genealogical family lists, drafts of his autobiographical

book, personal and professional correspondence, and medical articles and

publications.