Yehosha Yellin's memoirs, the manuscript of which is kept in the Central Zionist Archives, offers a fascinating glimpse into the way the residents of Motza experienced the British conquest of Jerusalm

The story of how Jerusalem surrendered to General Allenby is well known. Most of us are familiar with the story of Hussein al – Husseini, the mayor of Jerusalem, who had to walk all over town on the cold and damp morning of the 9th of December, 1917, and surrender again and again to every British soldier he chanced upon: two army cooks (that were just out looking for some eggs), two obstinate sergeants who refused to except his surrender and would only grant him a photo, their commander, and their commander's commander, who would not relinquish the honor he deserved. Jerusalem surrendered officially two days later, but Al – Huseini did not witness the occasion. The poor man, worn out from ceremoniously standing in the cold for so long, came down with pneumonia and died shortly after.

The official ceremony is also well known: the honorable general in his shiny boots, his grand entourage, all the city's notables, the king's horsemen and the flags of the British Empire. But there are, of course, other, more personal accounts of the British entrance to Jerusalem. One such account can be found in Yehosha Yellin's memoir, "Memories of a Son of Jerusalem". The manuscript of the book is kept in the Central Zionist Archive, and serves as a first-hand account of the events.

Yellin's book, first published in 1924, is considered one of the most important books about 19th century and early 20th century Jerusalem. One of the chapters tells the story of the residents of Motza, (of which Yehosha Yellin was one of the founders), when the British Army was nearing Jerusalem.

"Lest our homes be our graves"

On the 31st of October 1917 the British took Beer Sheva and started to make their way towards Jerusalem. For the residents of Motza, a difficult period began. Turkish soldiers posted in Bab Al –Wad, Abu Gosh and the Kastel started to flee from their posts to the mountains to the east of Motza. To the west of the Colony, the British were closing in, and the residents found themselves in the middle of the nightly fire fights between the two armies. During the days they hid in their basements and only at night, when the canons ceased fire, did they dare go up to their houses, "lest our homes be our graves", as Yellin writes. On the 20th of November, when the British reached the Kastel, the situationbecame worse, and the residents were cut off from Jerusalem. They had to buy all their supplies in the near village, and lived on bread and vegetables alone. But the most difficult thing, writes Yellin, was neither the hunger or fear of the canon fire, but dealing with the nightly raids of the Turkish soldiers, who came looking for food, and forced the people of Motza to hand over dear and scarce supplies by force of arms." My daughter, so afraid of the soldiers, came down with malaria, and lay in bed six days without a doctor, until a young boy from the near village agreed to go to town and bring her medicines from the doctor (I had to describe her sickness in writing), and so she became well,"' writes Yellin of the ordeal.

In the upcoming days the raids and the fighting in the area intensified, and the residents decided to leave their homes. They rented rooms in the nearby Arab village. This did not help Yellin, who took his kettle with him. At night, the soldiers appeared in the village, and forced the woman whose home he was staying at to give them his biggest cow. The frightened woman woke the whole village. The fear of the soldiers united the Arab villagers and their Jewish guests and they decided to send a delegation of two Arab women and two Jewish women (the men were mostly army deserters), to the military governor in Dir Yassin, and ask for the Army's protection. But this did not end their plight. On 12th December, the Turkish army issued an evacuation order from Motza and its nearby Arab villages. The area was defined as a military zone and all residents were to leave in twelve hours in order to make way for the great battle between the Turks and the British planned for the 3rd of December. "You can imagine", Yellin addresses his readers, "the great confusion and commotion among the residents. Neither of us slept a wink all night".

David Yellin's home in Motza in more quiet times. Yellin - upper right. (PHG\1023889)

In the morning there was a great commotion. The people of Motza and the villagers nearby tried hurriedly to hide all their belongings in one of the caves in the area: furniture, wall clocks, pottery and linen. Everything else had to be hauled to Jerusalem or it would be lost forever. Yellin, already an old man suffering from arthritis, had recently lost his donkey and had to shuffle his legs until he found a new donkey, albeit a lame one, and porters – all exorbitantly priced. He finally made it to Jerusalem with his daughter, her husband and their three children.

In Jerusalem the Yellins settled in the house of David Yellin, who had been exiled to Damascus by the Turks at the beginning of the War, and would only return in 1919.

Two weeks after the flight from Motza Yellin wrote in relief: "in Parashat 'Miketz' ('The End') the city was conquered by the British, and the Turkish rule came to an end. Then I said, jokingly, how the order of the Parshiyot fitted the order of events: in 'Vayishlach' ('And he shall send') we were sent from Motza, and in Parashat 'Vayeshev' ('And he shall settle') we returned to Jerusalem and settled in it. In parashat 'Miketz' the Turkish Government came to an end and our troubles, as well as the troubles of all the people of Jerusalem, ended as well". And he ended hopefully: "May the Almighty hasten the end of our people's exile, and return it to our homeland, and gather us all from the four corners of the land, and may we live to see the redemption of Judea and Jerusalem, Amen!"

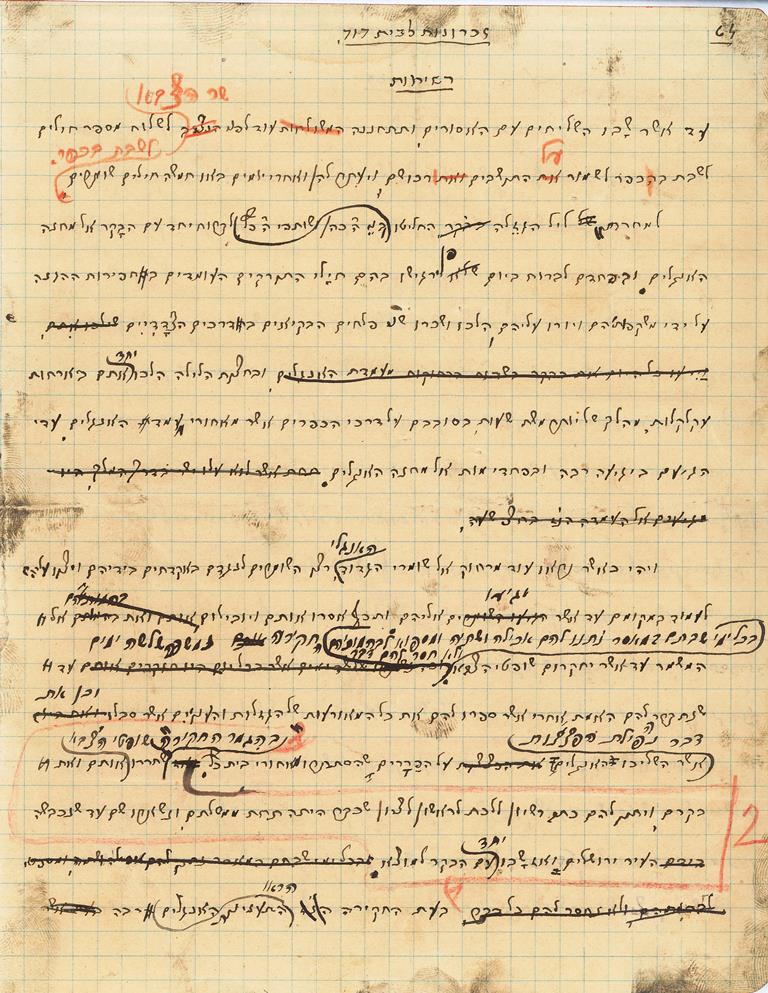

The menuscript of "Son of Jerusalem". (The book's working title). (A200\9)

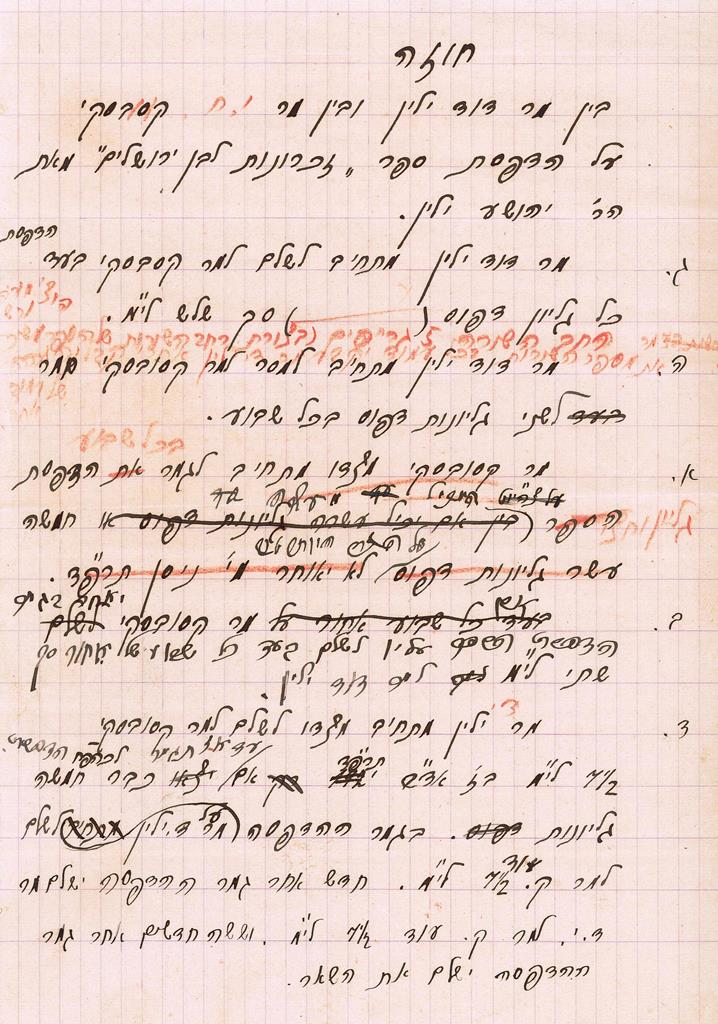

The contract signed beween David Yellin, Yehosha's son, and the book's publisher. the book was published in 1924 (A200\9)

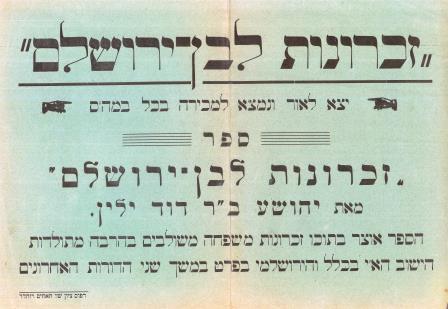

A poster announcing the publication of the book (A200\9)