The crystallization of a modern Jewish national consciousness at the end of the 19th century and the early 20th century, that the Zionist movement is its end result, brought with it some cultural trends, such as a growing interest in Jewish heritage. An example of this trend is Bialik's and Ravnizky's Book of Legends that deals with stories from the Talmud. Another example is Druyanow's Book of Jokes and Antics.

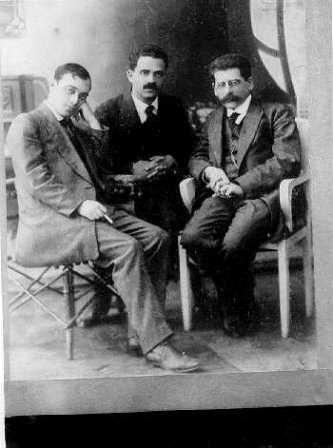

In 1909, Altar Druyanow, the Jewish writer and journalist, was hospitalized in a sanatorium in Dresden and suffered immensely – not from physical illness, but from boredom. A gift he received from a friend helped ease his misery - a little book of Jewish jokes in Yiddish. Druyanow spent his days in the sanatorium immersed in the book, and emerged with a new goal. He decided to create a broader, definitive compilation of Yiddish Jewish jokes. During the next few years, he carried a notepad and a pen at all times, and wrote down every Jewish joke he heard. He also issued requests in Jewish newspapers, asking readers to send him jokes and folktales. He collected, compiled, rewrote and translated the material into Hebrew, and in 1922 the first, single-volume edition of the compilation was published in Frankfurt. A complete, three volume edition of the book was published in Tel Aviv in the years 1935-1938.

Druyanow saw the Book of Jokes and Antics as much more than a mere compilation of jokes. For him, it was an ethnographic work that delved into a less familiar aspect of Jewish life in Europe. The Jewish tradition was always characterized by an ambivalent stance towards humor - it perceived it as part of the everyday pleasures of life. This is why it was left out of Jewish canonical works. Folktales and jokes were an alternative source of expression and were not, to a large extent, put down on paper. Druyanow saw this medium as a means through which the "real", authentic Jewish identity shined through.

If official sources represent the idealized version of the society of which they speak, the way it would like to see itself, alternative sources tell of the reality behind the imagery. The Book of Jokes and Antics describes the everyday life of the Jewish European diaspora without filters and with no mercy. Its heroes are full of flaws, petty, ridiculous at times and not always moral. The humor of most of the jokes does not stand the test of time and not all of the social contexts they depict are easily understood today. But the cynicism that marks them will not be lost on the modern reader, and they still hold their power as a medium for tongue–in –cheek self-criticism.

The drafts of The book of Jokes and Antics, the pads that Druyanow carried wherever he went, are kept, in part, in the Zionist Archives. Droyanov's personal archive also includes other manuscripts, such as that of The Tel Aviv Book, and articles he wrote for Jewish press in Israel and abroad. The CZA also holds the Druyanow collection – a unique collection, unusual in its scope, which consists of early Zionist documents that Druyanow collected during his Zionist activity.