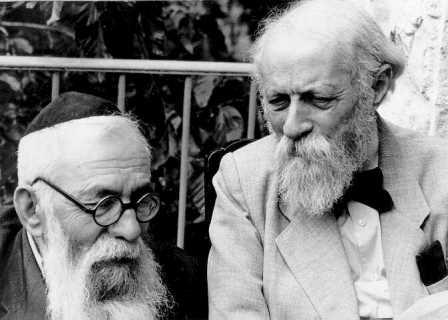

Rabbi Binyamin, (Yehoshua Radler-Feldman), an intellectual associated with left-wing currents and religious Zionism, was a man of contradictions. A glimpse into the mind of a man who believed that only love would save the people of Israel.

Rabbi Binyamin (Yehoshua Radler-Feldman, 1880-1957), was born in Galicia, then a part of the Austro-Hungarian empire, to a traditional Jewish family, that was close to European culture. He studied in a Jewish heder, and later at a university in Germany, and so was immersed in both cultures. This ability, to fuse two seemingly contradictory worlds, later enabled him to develop unusual and independent ideologies, stemming both from Jewish tradition and humanitarian liberalism.

Rabbi Binyamin started showing scholarly inclinations at an early age. As a young boy he spent hours reading in Hebrew and German. A testament to his independent way of thinking can be seen in the fact that at this time he began to present himself as "Radler–Feldman", a combination of his own last name and his mother's maiden name, an unusual practice at a time when feminism was still an innovative concept. His intellectual career began in 1901, when he traveled to Berlin to study agriculture. There, after meeting Hebrew writers, his interest in Zionism began, and in 1902 he published his first article. Feldman became an ardent Zionist, and was active in organizations that helped students immigrate to Palestine. At that time he founded the monthly paper Keshet – the first Hebrew illustrated magazine.

In 1906, after completing his studies, Radler-Feldman moved to London, where he met Yosef Haim Brenner. This was the beginning of a long friendship. Radler-Feldman and Brenner worked together on the journal "Hameorer", a literary journal that was active for only one year, but had a profound influence on Hebrew literature. The cream of the Hebrew literary milieu took part in the project: Deborah Baron, Hillel Zeitlin, Zalman Shneor, Micha Yosef Berdichevsky, and others. Brenner and Radler-Feldman published their own work in the journal. At that time Radler-Feldman began signing his writing as "Rabbi Binyamin", a pseudonym he kept from then on. The professional relationship between Rabbi Binyamin and Brenner grew into a personal friendship, and when Brenner wished to immigrate to Palestine, but was a penniless Russian migrant, Rabbi Binyamin gave him his passport, and Brenner came to Palestine under Radler-Feldman's name.

After a year in London, Rabbi Binyamin moved to Romania, where he continued his Zionist activities, and used his agricultural education to organize training for new pioneers. It seems that this is where he conceptualized his unique ideological outlook. In 1906, while he was still in Romania, he published an article titled "The Arab Burden”. The article is a pan-Semitic manifesto, imploring the Jews to fulfill the return to Zion in its holistic sense. He believed that the Jews were not returning to their homeland in the geographic sense of the word, but that the "return" was a spiritual one - a reclaiming of their moral role as a "light unto the nations". And so they should proceed peacefully, and with justice. "It is not with enmity or venom that you will build you home, but with love, justice and faith". "Love the inhabitants of the land for they are your brothers, of your flesh”. So writes Rabbi Binyamin regarding the Arab question. He bypasses the great moral obstacle facing the Zionist movements – the Arabs of Palestine – by defining Judaism not as a religion, but as an ethnicity. This enables him to define the Arabs and Jews not as adversaries but as brothers. The result of this return is not a war between two religions or two nations, but the completion of the multi- cultural puzzle that is the Middle East. Rabbi Binyamin goes even further - he does not see the Arabs as a threat, to such an extent that he calls for marriage between Arabs and Jews. According to him, an Orthodox Jew, this would not be assimilation, but a natural connection. The Arabs, Rabbi Binyamin believed, would welcome the Jews with open arms, if they would bestow upon them their knowledge in agriculture, education, and more. The two nations would march towards a better future, where they would live together happily.

This approach can be explained as a result of a life in what was a multi- national empire at a time when the Spring of Nations in the Austro- Hungarian Empire, the revolutions of 1848, was yet to be translated into demands for national independence. It was a time when a union between different national groups was considered possible. It would not remain in accordance with the times, when national awakening was comprised of demands for sovereignty and self-government. His philo-Semitic outlook, despite the emphasis on justice and humanity, was a combination of paternalistic and utilitarian perceptions: colonization with an attempt to appease the "natives". The vision he drafted in "The Arab Burden" was not a real bi-national vision. Rabbi Binyamin's ideological vantage point was the belief that what would determine the extent to which the Arabs would accept their own transformation into a minority, through massive Jewish immigration, of which he was an ardent supporter, would be the way in which they would be treated by the Jews. At the basis of his vision of peace was a disregard of the Palestinian national movement – a movement that demanded hegemony, not equality - just like Zionism and every other modern national movement.

In 1907 Rabbi Binyamin came to Palestine, and settled in Petah Tikvah. In the following years he was engaged in many Zionist activities: he was among the founders of the Kibbutz Kinneret, and of Tel Aviv and Bat Yam, took part in the founding of various neighborhoods in Haifa and Jerusalem, was among the founding members of Kfar Etzion, and more. He worked in the Palestine Office in Jaffa, where he worked on bringing the Jews of Yemen to Palestine. He was also a member of Brit Shalom, as well as the Hebrew Vegetarian Association. During this time he wrote in many Hebrew papers, Ha'aretz, various journals of the Zionist factions, and others. He founded the Hazofe newspaper as well as the journal of Brit Shalom, the political journal Ner, and authored a number of books.

Rabbi Binyamin was immensely bothered by the "Arab question" and its implications on Zionism's moral future. His writings, which are kept in the Central Zionist Archives, paint a picture of a man with unique beliefs, sometimes seemingly contradictory, and almost always opposing the mainstream Zionist outlook. An example to that can be seen in an article that he wrote in 1957, entitled: "Yes to the State of Israel, No to the State of Ben Gurion". In this article he expresses his concerns regarding the political path of Ben Gurion. He writes: "The state of Ben Gurion is not simple and modest as we envisioned, but idealistic- religious- messianic. Prophets foresaw it…, generals armed it with weapons. The crows bring it bread and meat in the morning and evening, like that old prophet by the dry river. They bring luxury cars, planes, cannons without end." Beyond the clear anti-militaristic criticism, it is remarkable that this religious man criticizes the use that the leadership made of religion.

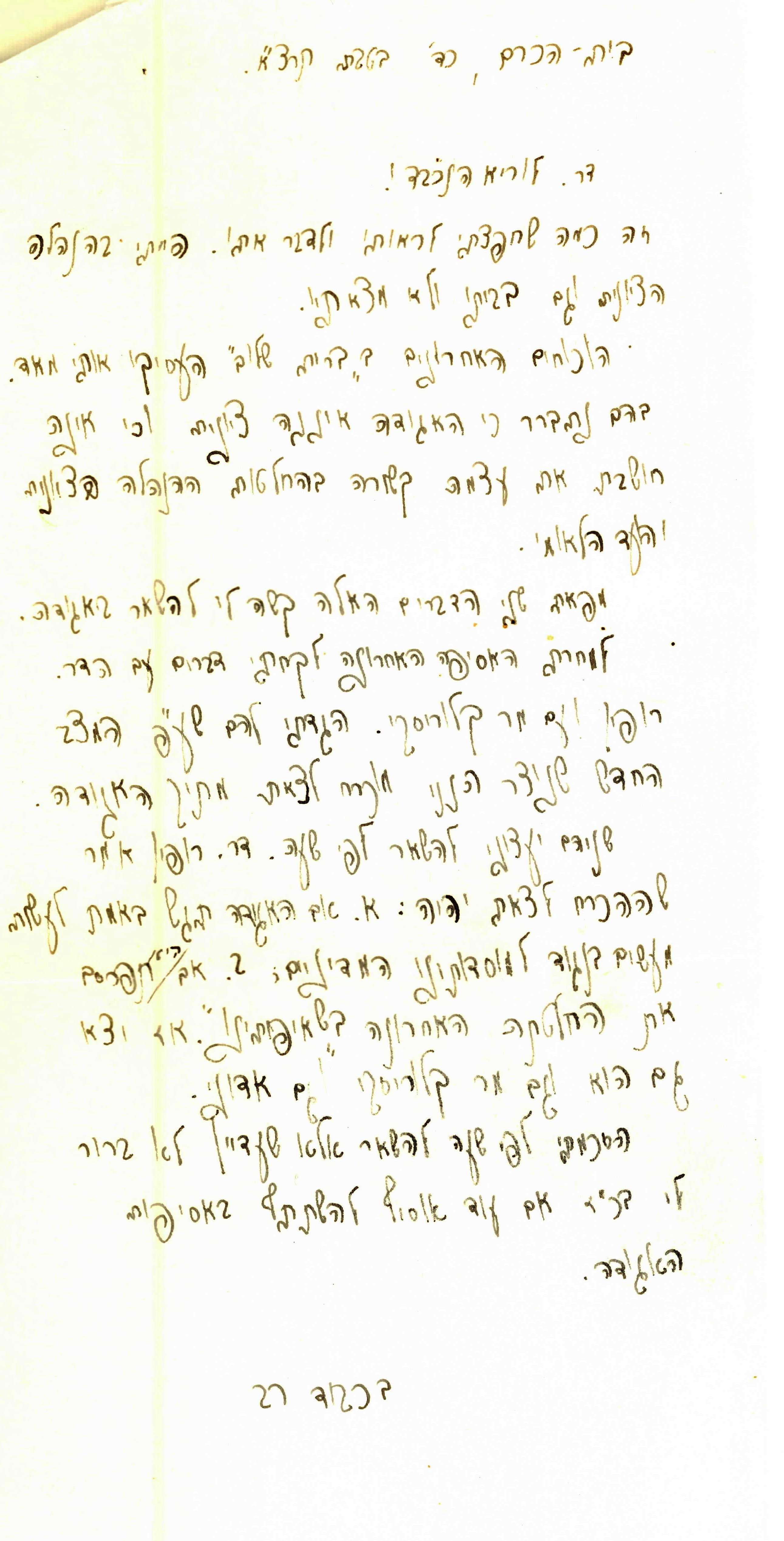

Until the end of his life Rabbi Binyamin continued to criticize Israeli leadership from the leftist wing. In a speech that he made in the early 1950's, for example, he spoke of the "Dir Yasinism" that is becoming prevalent in Israeli society. At the same time he also wrote extensively about the role of Jewish tradition, as in an article before 1948, where he spoke to an anonymous Jewish woman on the importance of observing the Sabbath. A sign of the complexity of his ideas, and of the extent to which he found it hard to find a proper framework for his ideas, can be seen in the way in which he resigned from Brit Shalom: "The recent debates in Brit Shalom are very much on my mind." wrote Rabbi Binyamin to Dr. Laurie, the chairman of the association. “I realized that the association is not Zionist. This makes it very hard for me to stay a member of it.”

It seems that the collective Zionist memory has forgotten Rabbi Binyamin. Maybe the reason is his political outlook; maybe it is the complexity of his ideas and his unwillingness to conform to any one ideological category. The documents before you offer a small glimpse of the thinking of a man who believed that only peace and fraternity can guide Israel on the path to righteousness and justify its existence. As he wrote in “The Arab Burden”, “Great and deep are the ways of love. Its depths are yet to be delved into. Close it and it will never again open. Open it and no force could ever close it again.”

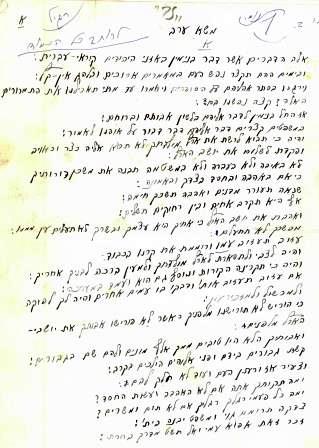

Here is a small sample of R' Binyamin's archive.

R' Binyamin was a strong believer in learning the Arab's culture and language. This is a page from his Arabic notebook.

"Alternative peace plan".

An apeal to the Arab leadership, where R' Binyamin asks that the Jews be let into Jordanian contrloed Gush Etzion to visit graves of their loved ones that fell during the 1948 war.

R' Binyamin sometimes recieved "fan mail' such as this- an anonymous letter branding him a traitor and an heretic.