Hillel Cohen's recent book: Year Zero of the Arab-Jewish Conflict 1929, follows the circumstances of the bloody 1929 riots in Palestine and offers a new outlook on the events

On June 8th, 1935, Hapoel Tel Aviv held a game in honor of recently freed prisoner Simha Hinkis, a policeman who was imprisoned by the British authorities for his involvement in the 1929 riots and freed after six years. The stadium was packed, the band was playing a cheerful tune, and the crowd held its breath while Hinkis made the opening kick. The crowd roared – it was the final chord of a week-long carnival surrounding the prisoner that included a festive reception in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, a meeting with Rabbi Kook, a party in the Maghrebi Cinema in Tel Aviv, and a job offer from the municipality of Tel Aviv. Clearly, the Yishuv honored Hinkis. During his trial, that ended in a death sentence, later turned into a prolonged imprisonment that ended early during a pardon, Hinkis was turned into a national hero. For the Yishuv, he became symbol for Arab murderous violence, as well as for British rigidity against the Jews. But who was Hinkis, and why was he imprisoned?

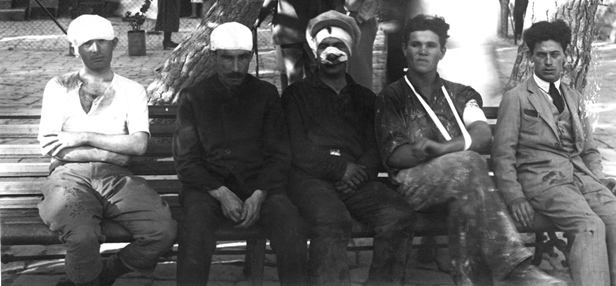

Victims of the 1929 riots. From the Hadassah hospital archive (PHG\1410634)

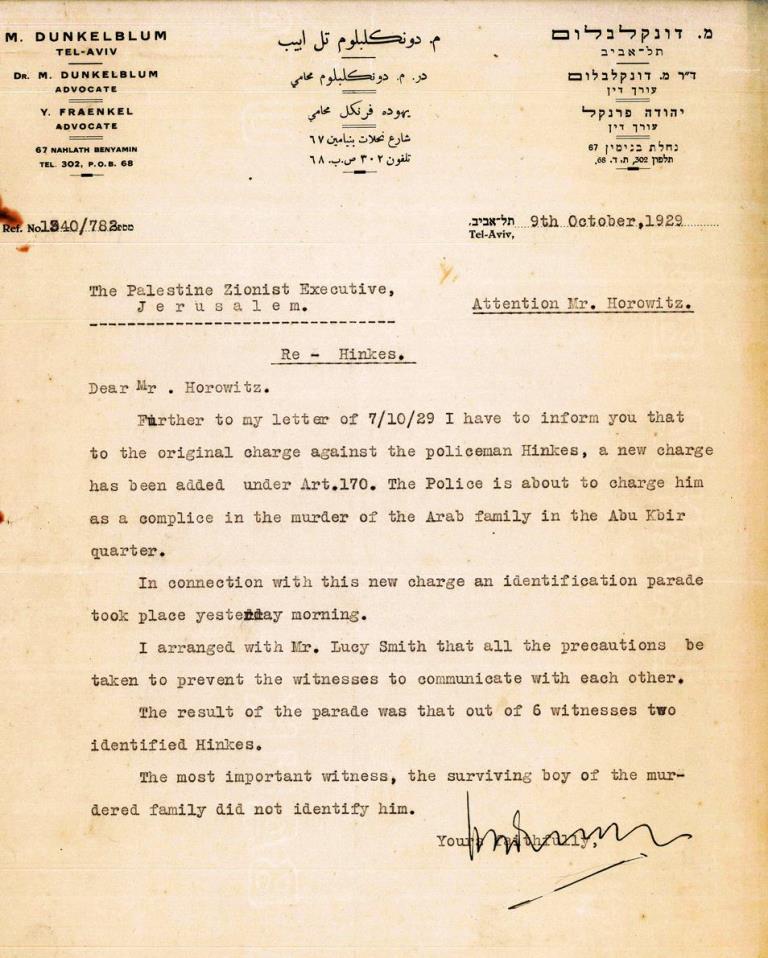

The memory of Hinkis faded from Israeli collective memory along the years, but Professor Hillel Cohen, a researcher at the department of Middle Eastern Studies at the Hebrew University, met him again in the pages of the Geographical encyclopedia by Jaffa born historian Mustafa Murad al – Dabbagh. In an episode regarding the 1929 riots, al – Dabbagh writes of the murder of a family from Jaffa – the family of Sheikh Abd al – Ghani Awn, Imam of the Abu Kabir mosque, by a Jewish policeman. Cohen was surprised. "At first", he says, "I had my doubts". He began to research the subject. Another document he found in the Haganah archive confirmed al – Dabbagh's version of events: officer Hinkis shot the Awn family – three men and two women. Two children – a five year old and a two month old baby were wounded. Another nine year old survived by hiding under the dead body of his mother. "Learning about this murder prompted me to write the book", says Cohen. "I understood that although the story surprised me, Palestinian readers would not be surprised. I assumed that there are more things about the 1929 riots we don't know about, and decided to look for them".

Cohen's book is an unusual one in the body of Israeli Historiography. It aims to analyze a founding myth of Israeli society from a new perspective – one that takes into account both the Jewish – Zionist and the Palestinian outlook on events. "I try to hover above national truths. My own, as a Jew and Zionist, as well as the Palestinians". In a sense, the book deals with the history of emotions - how the Palestinians experience the riots, and how the Zionists experience them. My goal is to understand how people, as individuals, experience this historical event. It was important for me that the book will not be meant for academic audiences exclusively, but to anyone who is willing to be exposed to complex historical thinking". Cohen utilizes a wide variety of resources in Arabic and Hebrew. In the Zionist Archives, he mainly used the file of the legal committee that was established to investigate the riots. The result is a complex book, full of anecdotes and testimonies of people that experienced the riots from both sides. It offers the reader in simple, fluent language, a multi-faceted version of events, much more that the prevalent one.

Letter to the Zionist Executive regarding Simcha Hinkis's case (L59\68)

God and the devil work side by side

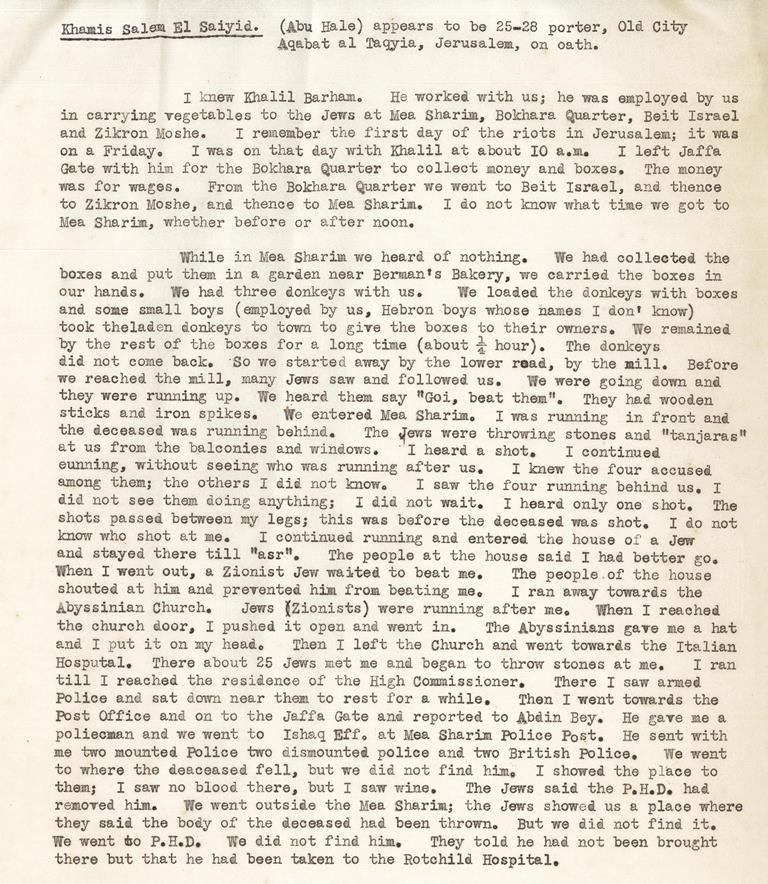

Cohen, it's important to say, is no trying to create a revision to the common historic Israeli narrative, according to which 133 Jews were murdered by Arab rioters, most of them while seeking refuge in their own homes. Most of the Arabs killed in the riots, he says, were killed while taking an active part in them. But he illuminates an unknown part of the story: lynches were perpetrated by Jews against Arabs as well, and the Hinkis case was not one of its kind. This is the conclusion from his review of the first day of the riots in Jerusalem, Friday the 23rd of August, for example. On one thirty that day, after the Friday prayer, the Arab rioters left al – Aqsa mosque, heading for various directions, and the riots erupted. According to the classic Zionist narrative, it was the mufti of Jerusalem, Haj Amin al- Husseini that provoked the prayers. Hillel doesn't doubt that version directly, but he gives another, alternative interpretation of the events of that day: in the forty five minutes preceding the emergence of the rioters from al- Aqsa, on two different occasions, three Arabs men were attacked on Mea Shearim, a neighborhood in Jerusalem, by Jews. Two of them were porters passing the neighborhood on account of their jobs. One was murdered; the other one escaped and found refuge in the home of a Jewish family. A third man, coming to the neighborhood for business, was also attacked and killed. Were those Arab men the first victims of the riots? Did rumors of these murders reach the worshippers of al – Aqsa and cause them to begin rioting and murdering Jews as vengeance? Cohen lets the readers answer that question for themselves. Tensions were high on both sides at the time, he says, and any conclusive answer, he claims, will serve as propaganda more than historic truth.

The question of the rescuers is dealt with extensively in the book. Where there are bloody riots such as these, writes Cohen, there are also heroic rescues. And in 1929, they were not a rarity. God and the devil, it seems, were working side by side that week. One such case Cohen describes is that of Abu Shaker Amru, that lived during the riots near the Romano House. At the height of the Hebron massacre, Amru ran to the house of his neighbors, the Slonim family, laid down at the entrance to the house, and so prevented the attackers from entering and lynching the family hiding inside. The 75 year old man refused to budge, even when one of the attackers slashed his leg with a knife. Interestingly, the Arab press of the time, that glorified the riots as a national uprising, didn't treat the rescuers as traitors, but praised them. "The Arab press's treatment of the rescues points the contradictions every national movement has to deal with", says Cohen. "We can see this phenomenon in Israeli society as well: everyone likes to boast when an IDF soldier gives water to a wounded Palestinian child. But every conflict has another, violent side."

Year zero of the conflict

But apart from shedding light on less known aspects of the riots, Cohen examines some fundamental influences the riots had on the Arab- Israeli conflict. 1929, according to Cohen, is year zero in the conflict in a number of aspects, and above all, in the aspect of collective awareness. "The 1929 riots have become a symbol in Israeli consciousness for Arab murderousness", he says. One of the main arguments of the book is that the worldview of the generation that fought in the 1948 war was forged by the trauma they experienced during the 1929 riots. One of the most harrowing testimonies in the book stands as an example: the testimony of Shmuel Tvania- Shivli that survived the massacre at the Gurji courtyard as a baby, after being left for a whole night at the morgue, held by his dead mother, after having being mistaken as one of the dead. Tvania, who joined the Lehi and fought in Nablus gate during the 1948 Arab-Israeli war, explains the way he perceives the conflict, sixty years later: "there are murderers named Arabs, and they will never like Jews, and there will never be peace with them." Yisrael Tal, founder of the Mercava tank, whose family was attacked in Safed when he was five years old, describes that he felt as if he was avenging the attack on his family every time he shot an Arab fighter during the 1948 war.

Eye witness testimony regarding the lynches in Mea Shearim (L59\114)

Cohen claims that the 1929 riots were the first collective trauma that the Yishuv experienced, a trauma that shaped its collective symbolic infrastructure: the Arab aggressor, on one side, opposed by the besieged Jew, that never has anyone to lean on but himself. The development of this outlook had two intertwining consequences. Politically, the riots brought all talks about a Zionist integration in the Arab world to an end. "The 1929 riots", Cohen says, "caused a break with Pan – Arabism. Those elements in the Yishuv that dreamt of integration into the Arab world realized that this vision will not come to pass". On the practical level, the riots facilitated the creation of the security ethos In the Yishuv. From the riots onwards, up to this day, the Yishuv, and the state of Israel after it, will be in a state of permanent readiness for war – with all its moral and political implications.

But Cohen recognizes another result of the riots. In the Zionist discourse, there is a tendency to speak about the way Zionism "created" Palestinian nationalism. Cohen identifies a reverse phenomenon: the rioters, he says, attacked mainly Sephardic Jewish communities that lived in Palestine side by side along the Arab community for many years. Communities that, for the most part, did not identify with the Zionist movement. "But the Arabs read the map better", says Cohen. They understood that the moment Zionism entered the equation, the rules changed. A barricade was erected between the local Jews and Arabs. "In the 1929 riots, the Palestinians said to the Sephardic Jews: you have to choose. You're either with us or against us. In this sense, this community experienced the greatest trauma in the riots. The events of that week of August brought to an end the original outlook of the Sephardic community in Palestine that saw the Palestinian Arabs as brothers, and strived to uphold their rights in the face of Zionist immigration. In a way, the riots erased the identity of the "Jewish Arab", because this community understood that in order to survive they must integrate into the new Yishuv, in which this identity had no place". The riots, says Cohen, were the melting pot that transformed the divided Jewish Yishuv and created the base for the Israeli society we know today. A society divided into different social groups, but united by the same values, symbols - and fears.